BACK HOME

Shawn Ford

SLS 460

Final Paper

Spring 2001

Note: The following paper was written as the final

project for SLS 460: English Phonology, instructed by Professor Richard Schmidt,

at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. I must thank Susie Mercado for her portion

of the contrastive analysis group project. The contrastive analysis is by no means

comprehensive, yet it presents some of the most common differences between English

and Japanese phonology. The font "IPAPhon" was used to produce the phonemes

throughout this paper. For some reason, several of these characters are not web-readable,

resulting in their ommission or their replacement with a wrong character. Please

pardon any errors or omissions.

Contrastive Analysis of English

& Japanese

and Tutorial Report Final

INTRODUCTION

Within the field of linguistics a number of studies exist that compare the differences

between the English and Japanese languages. Not only are the lexical, orthographic,

and syntactic systems very different, but the phonological systems of the two

languages also stand in stark contrast to one another. In the following paper,

I will give a brief contrastive analysis of selected features of the phonological

systems of English and Japanese followed by a report on my tutoring project.

Due to the nature of this project, I will limit my contrastive analysis to only

a few of the phonological aspects of the languages in comparison. Therefore,

I will briefly consider certain articulatory settings before devoting most attention

to the phonemic inventories of the languages. Afterwards, I will try to predict

difficulties that native speakers of Japanese might have learning English as

a second language based on my comparison of English and Japanese phonology.

Finally, I will give a report on my tutoring project from this semester using

my contrastive analysis as a guide.

ARTICULATORY SETTINGS

English and Japanese have very different articulatory settings; therefore, it

may be difficult to gain high levels of proficiency in the pronunciation of

one of the languages with the previously developed articulatory setting of the

other language. These differences may account for the challenges that speakers

of either language may have when learning the sound systems of the other language.

One of the major articulatory differences between English and Japanese is regarding

the lips. Hattori (1951), cited in Vance (1987) says that in Japanese “the

lips play almost no active role in pronunciation; they are neither rounded nor

spread, but neutral” (p. 7). Lip rounding in Japanese is much weaker than

in English. This contrast in articulation results in some of the phonemic differences

between the two languages.

Perhaps the most problematic articulatory difference between English and Japanese

may be found in tongue placement. Vance (1987) cites Honikman (1964) regarding

tongue positioning in English to explain part of the difference. According to

Honikman, “The tongue is tethered laterally to the roof of the mouth by

allowing the sides to rest along the inner surfaces of the upper lateral gums

and teeth” (p. 7) and the tip of the tongue is free to move. As a result,

alveolar consonants are more frequent than any others in English. On the other

hand, in Japanese pronunciation the average position of the tongue is quite

far back in the mouth, with the body of the tongue shaped to the roof of the

mouth, dorsum somewhat raised, and tip behind the lower front teeth. As a result,

velar consonants are more frequent than the other consonants in Japanese, and

they occur more often than in English.

CONSONANT INVENTORIES

When examining the consonant phoneme inventories of English and Japanese, it

appears that the two languages are very similar. Upon closer inspection, the

similarity lies in the fact that nearly every Japanese phoneme is also found

in English. In fact, the only phoneme that clearly is not found in English is

the bilabial fricative /ƒ/. In contrast, several

English phonemes are non-existent in Japanese. These phonemes are mainly within

the fricative domain.

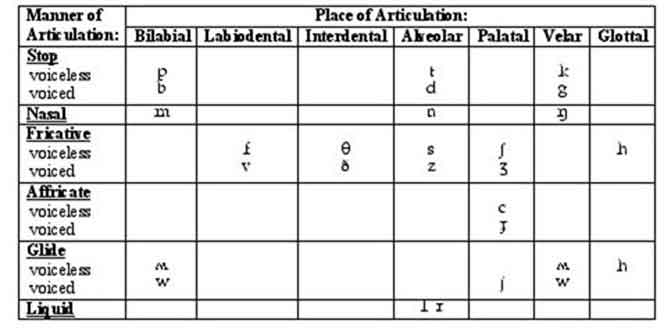

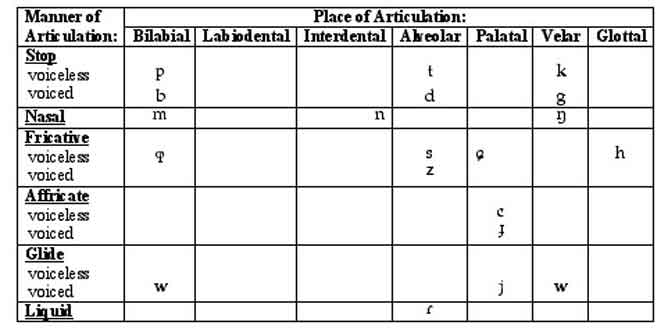

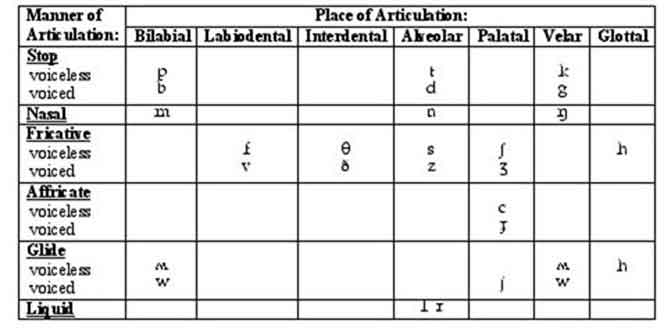

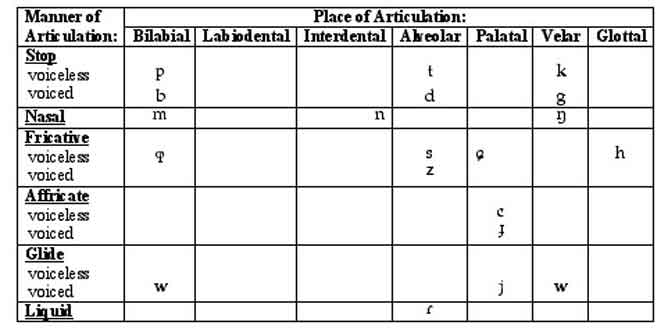

The following two tables are provided to aid comparison of English and Japanese

phonemes. Table 1 lists English consonant phonemes and Table 2 lists Japanese

consonant phonemes. Both tables use the most current International Phonetic

Association alphabet to represent phonemes and are modeled after a phonetic

table provided by Fromkin and Rodman in An Introduction to Language, sixth edition

(p. 233). The phonemic inventory of Japanese is taken from Vance (1987).

Table 1: English Consonant Phonemes

Table 2: Japanese Consonant Phonemes

Before beginning my comparison of English and Japanese phonemes, it should be

pointed out that within the literature of Japanese phonology, there appears

to be considerable discrepancies regarding the phonemes of the language. Several

of these discrepancies may be explained simply as differences in symbols used

for transcription. I overcome this problem by strictly following the IPA standard

alphabet throughout this paper.

The greatest challenge comes from the fact that researchers seem to have different

opinions about what constitutes a phoneme in Japanese. According to Vance (1987),

there are two extremes of thought concerning the Japanese phonetic system: the

conservative variety and the innovating variety. The conservative variety,

supported by Vance, relies mainly on the minimal pair rule of linguistics for

determining phonemes. The innovating variety, advocated by several Japanese

linguists as well as other western linguists, appears to consider numerous allophones

to be phonemes. This view seems to be based partly on minimal pairs, partly

on dialectal differences, and partly on commonly used loan words with non-Japanese

sounds. Examples of some of these sounds considered phonemes in the innovating

approach are /ç/, /µ

/, and /z/ (Vance). In our consideration of Japanese

phonemes, we will follow the conservative variety as described by Vance in an

attempt to avoid possible confusion between phonemes and allophones and to limit

our analysis and discussion.

STOPS

There are six distinctive stops in Japanese: the bilabials /p,b/;

the velars /k,g/; and the alveolars /t,d/. However,

the production of /t,d/ in Japanese is quite different

from their English counterparts. The tongue is very flat and convex to the roof

of the mouth in the Japanese /t,d/, and the blade

of the tongue touches the alveolar ridge; whereas in English, only the tip of

the tongue is curled up to and touches the alveolar ridge, slightly concave

to the roof of the mouth. Due to the differences in articulation of these stops,

there is much less tongue tension in the Japanese sounds.

NASALS

English and Japanese both contain three nasals: /m/,

/n/, and /h/. /m/

and /h/ are articulated in the same places in both

languages and have basically the same sound qualities. However, the /n/

in Japanese is produced with the tip of the tongue against the back of the front

teeth, whereas the English /n/ is alveolar. Although

the place of articulation is slightly different, the resulting phoneme is not

noticeably different.

FRICATIVES

As mentioned previously, the major difference between the English and Japanese

consonant phoneme inventories lies in the disparity of fricatives found in the

languages. English has nine phonemes, while Japanese has only five. This fact

proves to be a major source of problems for Japanese learners of English.

In Japanese, the voiceless, bilabial fricative- /ƒ/

is the first sound in fune “boat”. /ƒ/

is somewhat like a cross between the English phonemes /f/

and /h/. This sound occurs only before /u/.

This is not likely to cause any problems for Japanese speakers learning English,

or English speakers learning Japanese, as using /f/

or /h/ in its place is not likely to create much

confusion. However, it should be noted that confusion occasionally may arise

when Japanese mispronounce English words like “who” as foo

and “hula” as fura when they make the improper sound substitution.

The alveolar fricatives /s,z/ in Japanese are basically

the same as their English counterparts, except in the passageway that the air

travels when producing these phonemes. In Japanese, the air escapes through

a narrow central pathway from the back of the oral cavity to the front between

the tongue and the roof of the mouth. On the other hand, in English the tongue

is flatter so air escapes through a wider and flatter passageway.

The Japanese voiceless palatal fricative /Ç/

is similar to the English phoneme /ß/, but

the Japanese version is produced slightly more towards the back of the mouth.

Its voiced counterpart, /z/, is not used by all

speakers of Japanese; therefore, it is not considered a true phoneme. The glottal

fricative /h/ in Japanese is almost identical to

its English counterpart in its place of articulation and sound quality.

The major differences in fricatives of the two phonemic systems in question

are that Japanese lacks the English voiced labio-dental fricative /v/,

the voiceless interdental fricative /q/ and its voiced

counterpart /d/, and the voiced alveolar /zj/.

According to Vance(1998), none of these phonemes appear in the Japanese language

in native words, in borrowed words or as allophones of other phonemes. This

is very interesting since all of these phonemes are fricatives.

AFFRICATES

Another group of Japanese consonants that are produced further back in the oral

cavity than in English are the palatal affricates /c,Ô/,

which are related to English /tß,dzj/. While

they do have slightly different places of articulation and sound quality, the

differences are so minor that they are barely noticeable.

LIQUIDS

The English language contains two approximants: the lateral /l/

and the retroflex /®/. English relies on the

contrast of these two phonemes to distinguish between many minimal pairs in

the language. On the other hand, Japanese does not have two distinct approximants.

Instead, Japanese has only one, the alveolar flap /‰

/, that occasionally has [l] and [r]

allophones in certain dialects on certain occasions. This phonemic distinction

tends to be a problem for many Japanese speakers who are learning English.

GLIDES

The three glides of English and Japanese, bilabial and velar /w/

and palatal /j/, are considered almost identical.

They are made in the same places and have basically the same sounds except for

ever so slight differences as allophones with other phoneme combinations.

VOWEL INVENTORIES

Table 3 and Table 4 that follow are provided to ease comparison of the vowel

phoneme inventories of English and Japanese. The vowel charts represent the

oral cavity and give phonemes in the approximate place of articulation. The

charts are adapted after those found in Ladefoged (2001).

Table 3: English Vowel Phonemes Table

4: Japanese Vowel Phonemes

Japanese has five short vowels: /a/, /i/,

/u/, /e/, and /o/.

Although these vowels are somewhat similar to those in English, there are a

few differences. First, the Japanese low vowel /a/

is similar to the English /a/, but dialectical variances

may cause the Japanese /a/ to sound like the English and French /å/.

Second, the Japanese high front vowel /i/ is produced

with very little spreading of the lips. Unlike English, /I/

does not exist in Japanese. Third, the Japanese high-back vowel /u/

can be described as unrounded. In English this vowel is considered rounded.

Fourth, the Japanese mid-front vowel /e/ is close

to the English phoneme /´/. Finally, the Japanese

mid-back vowel /o/ is similar to the English /ø/,

the vowel in “saw”. According to Kawakami (1977) as cited in Vance

(1987), this vowel is “the only one in Japanese that involves active lip

rounding” (p.10).

Another interesting contrast between English and Japanese vowels is that the

perceptual effects of the vowels in the neighboring syllables are minimal in

Japanese. This means that unlike English, Japanese vowels do not seem to have

positional allophones, except for /u/. Each of the

five short vowels in Japanese have long counterparts, but they are not likely

to cause any major problems for learners of English. However, what may create

some difficulty for Japanese learners of English is the distinction between

tense and lax vowels (/iy/ vs. /I/;

/ey/ vs. /´/;

/uw/ vs. /¨/), because

such distinctions do not exist in Japanese. Japanese ESL learners may produce

sounds in between the tense and lax versions of the English vowel sounds.

There are also a number of allophones that exist in Japanese that are not found

in English. Such allophones, or phoneme-clusters, are likely to cause some degree

of difficulty for English speakers of Japanese. These include: [pj]

from the phoneme cluster /p·y/, a voiceless

palatalized bilabial stop; [ts] and [tß]

from /Ç·y/, a voiceless

palatalized alveolar affricate; [kj] from /k·y/,

a voiceless palatalized velar stop; [bj] from /b·y/,

a voiced palatalized bilabial stop; [gj] from /g·y/,

a voiced palatalized velar stop; [nj], a voiced

palatalized velar nasal; [ßj] from /s·y/,

a voiceless alveolar fricative; [zj] or [dzj]

from /×·y/, a voiced alveolar affricate;

[mj] from /m·y/,

a voiced palatalized bilabial nasal; [nj] from /n·y/,

a voiced palatalized alveolar nasal; [rj] from /r·y/,

a voiced palatalized alveolar flap; and [çj]

from the phoneme /h·y/, a voiceless palatalized

fricative. Another interesting contrast between English and Japanese is that

the corresponding phonemes of the allophones, as well as their phonetic descriptions

and occurrences, are quite different and sometimes even non-existent in Japanese.

PREDICTED LEARNING DIFFICULTIES

The assumptions I will present concerning the difficulties that a Japanese learner

of English may encounter with English vowel phonemes, are based on the idea

that learners tend to transfer their native language sound systems to their

second language environments. Where there are similarities in consonants, vowels,

clusters, or CV sequences, learners may not be as challenged as where there

are dissimilarities. For Japanese learners of English, I will predict that they

may replace English consonant or vowel sounds with the most similar Japanese

phonemes, allophones, or other sounds.

Japanese speakers seem to find /ßi/ very easy

to pronounce (as in “sherry”), but /si/

very difficult. In fact, loan words from English, such as shizun (season)

begin with /ßi/ instead of /si/ because of

the difficulty in producing [si]. When /s/

occurs before the high front vowels /I/ or /iy/

(as in “sip” or “sea”), Japanese speakers may pronounce

those words beginning with the sound as /ß/.

The reason for this is that the Japanese phoneme /s/

has the allophone [ß] in every instance before

/i/. Perhaps practicing the distinctions between

/s/ and /ß/ before

the two high front vowels using minimal pairs may help.

Another common problem among Japanese speakers

is the /v/ sound in English. This phoneme does not

exist in Japanese, so Japanese speakers may tend to substitute the phoneme /b/

for the unfamiliar /v/. Japanese ESL speakers who

make this substitution may want to practice distinguishing the bilabial /b/

and the labiodental /v/.

Japanese contains only one liquid /‰/ which

lies somewhere between the English /l/ and /r/.

Therefore, Japanese speakers of English may use the Japanese liquid for both

the /l/ and /r/ sounds

in English. This means that the words “right” and “light”

spoken by a native Japanese speaker, may sound like the same word. Moreover,

in the word-final position, Japanese speakers may delete /l/

and /r/ completely.

Japanese speakers have difficulty comprehending and pronouncing English consonant

phonemes that are nonexistent in the Japanese sound system. The two English

interdental fricatives /q,d/

are not found in Japanese and are often produced by Japanese ESL learners as

the alveolars /t,d/. While it may prove to be very

difficult for Japanese speakers to produce the interdental fricatives, it is

probable that a misinterpretation is unlikely to cause problems since many dialects

of English have /t,d/ as allophones of the two phonemes in question.

Regarding vowel phonemes, the English vowel sounds /æ/ and /\/

do not have counterparts in Japanese, and we predict that Japanese speakers

of English are likely to replace these with similar vowels in Japanese. The

vowel /æ/ may sound like the Japanese /e/,

/a/, or /aj/ depending

on the environment in which it occurs. Likewise, the English /\/,

when stressed, phonetically approaches the position of the Japanese /a/,

and when unstressed, the position of the Japanese /a/

or /o/. Therefore, /\/

may be replaced with either one.

The English /I/, as in “hit”, and /L/,

as in “hut”, tend to be replaced with voiceless, or partially devoiced,

/i/ and /u/ by the Japanese

speaker when these vowels occur between voiceless consonants (Kohmoto, 1969).

This is due to devocalization of high vowels in Japanese. For example, “substitute”

may be pronounced as /sLbst(i)tyu:t/

and “university” may be pronounced as /junivLs(I)ti/,

where (I) represents the complete or partial devocalized

vowel.

Consonant clusters occur much more frequently in English than in Japanese. The

general CVCV pattern in Japanese is often transferred to the consonant cluster

patterns in English, such that Japanese speakers may either insert vowels to

break-up consonant clusters or add vowels after word-final consonants. Additional

vowels such as /I/, /o/

and /u/ are likely to be inserted after consonants

that occur in the final position. These vowel insertions may or may not be partially

devoiced. Some examples of vowel insertion may include: /map:p(u)/ for “map”;

/ka:d(o)/ for “card”; and /tßatß(i)/

for “church”, in which case the /i/ may

be devoiced. Table 6 shows possible vowels that may be inserted after final

consonants in English words by Japanese learners.

Table 6: Possible Vowel Additions to Consonants in Final Position

I will also predict that Japanese speakers may tend to over-pronounce double

consonant sounds, namely stops, when they occur after short vowels in the medial

positions of English words. For example, a Japanese speaker of English may pronounce

“sudden” as /saddIn/, “kitten”

as /kittIn/, and “ribbon” as /ribbon/.

In Romanized Japanese, double consonants are usually spelled with double letters,

such as kippu “ticket” or yatto “finally”.

In English, double letters usually do not imply double sounds within words.

Japanese learners of English may need to be made aware of the fact that double

consonants usually do not result in a doubling of the sound in English.

The English voiced retroflex /®/ is nonexistent

in Japanese, as the Japanese liquid is the voiced alveolar flap /‰/.

Both the place and manner of articulation differs. The tip of the tongue touches

the alveolar ridge in the Japanese production of /‰/,

so its sound may be mistaken for the English /l/

or /d/. Furthermore, Japanese speakers may hear

and pronounce the English syllabic /r/ as /a/

or /o/, since the English /®/

is a sound somewhere between the Japanese /a/ and

/o/. In other words, the English word “four”

is likely to be pronounced /fo/ by Japanese.

Tutoring Report

SUBJECT

The subject for my tutoring report is an 18-year-old Japanese male. He has lived

in Honolulu, Hawaii, for the past two years. This period is the first time in

his life that he has lived outside of Japan. I have known him and have tutored

him since the second month of his arrival to Hawaii. When we first met, I would

classify him as a beginning speaker of English, although he studied English

in middle school and high school, as is the case with most children going through

the educational system in Japan. At this point in time, after several years

of language schooling and tutoring, I would place him at the low-intermediate

level in terms of production, but at the intermediate level in terms of pronunciation.

That is to say, his pronunciation is better than his production would suggest.

In my opinion, my subject is not very motivated to improve his pronunciation

or his English skills in general. Although he has improved quite a bit over

the last few years that I have known him, his ability seems to me to be less

than what it should be given the time spent and the exposure with the language.

A possible explanation for this could be that most of his friends are either

local Japanese or Japanese in Hawaii studying English; therefore, most of his

time is spent speaking Japanese instead of practicing English. I offer this

information just as reference for later discussion of his overall progress.

TUTORING SESSIONS

The sessions for my tutoring project were carried out twice per week for one

hour each session. My subject and I always met on the same days, at the same

times, and at the same place: Tuesdays and Thursdays, from 1:30 p.m. to 2:30

p.m., at the University of Hawaii Campus Center. This tutoring project encompasses

eight sessions totaling eight hours, from April 3, 2001, until April 26, 2001.

At the outset of the tutoring sessions, I set the following three goals:

1) Evaluate my subject’s problem areas regarding phonology;

2) Work on very limited and specific problem phonemes; and

3) Practice at least one suprasegmental feature that is a

problem for him.

At the beginning of this tutoring project I began by using minimal pair lists

that I made up myself before our tutoring session to diagnose problem areas

in my subject’s pronunciation. I chose words that I predicted would be

problems based on my contrastive analysis. For example, I gave my subject the

following words to help with my analysis: seat/ sheet, sit/ shit, this/ sin,

though/ dough, hood/ wood. I decided to use minimal pairs to begin with because

it is a procedure I was familiar with, and it seems to be fairly popular.

Also, I diagnosed my subject’s positional pronunciation of certain consonants

using the word list “Positional Occurrence of NAE Consonants” found

on page 373 of Teaching pronunciation: a reference for teachers of English to

speakers of other languages (Celce-Murcia et. al, 1996). I found this to be

helpful, and it forewarned me of problem areas before using the more comprehensive

word list given by the instructor later in the semester.

Next I used the “Diagnostic Passage and Accent Checklist” from Celce-Murcia

et.al (1996) to check for suprasegmentals. I chose this after a classmate suggested

it in class. While I liked the idea of diagnosing suprasegmentals through reading,

I felt that this passage contained too many difficult words and that pronunciation

errors could be blamed on reading ability. Afterwards, instead of reading, I

gave my subject a topic to talk about, and I looked for problems in his natural

speech. I think this proved to be more realistic and useful for both of us.

In addition to the reading passage to diagnose problems, I engaged in free-talk

time in order to examine suprasegmentals in my subject’s spontaneous speech.

Since I have known my subject for several years, I also know some of his interests.

I tried to begin each free-talk period with a topic that if interest to him,

such as surfing and music, and ask him open-ended questions to solicit casual

conversation. I felt that this was important to do because an analysis of a

learner’s speech only through reading has limited benefits. Reading a passage

may allow for a large amount of uninterrupted speech, but it is somewhat unnatural.

Also, errors found in pronunciation this way may be the result of reading problems

and not of phonological problems.

The last thing I used in my tutoring sessions was the word list of initial consonants

and final consonant clusters that the instructor handed out in class. This list

proved to be very useful for both of us. Not only was I able to find some of

his phoneme problems in a more orderly fashion, but the exercises proved interesting

and useful for my subject as well, if only for visually creating awareness of

his pronunciation problems.

Although my subject gave me his consent to record the tutoring sessions, I recorded

only two: the first session, and the seventh session. Through a combination

of factors the other sessions were not recorded.

OBSERVATIONS

Before beginning my formal evaluations of my subject’s pronunciation, I

first told him that I was going assess his production of English, and I described

how our following tutoring sessions would progress. Then I asked him to tell

me what he believed to be his major pronunciation problems: what did he think

were his problems, and what did he think other people felt about his pronunciation?

He first told me that he felt his biggest problem was that he sounded “too

Japanese.” I believed that he was referring to other’s perceptions

of his pronunciation. When I asked him to be more specific, he said that most

Japanese have a problem with /I/ and /®/,

/q/ and /d/, and “too

many sounds together”, meaning consonant clusters. He made no mention of

other consonants, any vowels, or any suprasegmental feature.

According to what my subject had just told me, I confirmed his problems with

the consonants that he mentioned by giving him a list of minimal pairs using

/t/ and /q/, /d/

and /d/, and /l/ and

/®/ that I had prepared beforehand. Then I had

him read minimal pairs to assess his /si/ and /ßi/,

and /b/ and /v/ distinctions.

All of these minimal pairs distinctions were predicted to be problems for Japanese

speakers of English. I asked him to read the words as naturally as possible

for him.

After doing further minimal pair exercises, my subject was surprised to find

out that he obviously had problems with these sounds as well. In every instance

possible, I gave him a few minimal pairs with the consonants in question in

initial and in final positions. In almost every instance, /t/

became /q/, /d/ became

/d/, /si/ became/ßi/,

/l/ became /®/ and

/b/ became /v/.

Although not an original goal of my tutoring sessions, I also noticed immediately

that he had very clear difficulties with certain vowels. My subject showed a

definite tendency to replace an English vowel non-existent in Japanese with

a Japanese vowel of close articulation. In most instances, my tutor replaced

/æ/, /ø/, and /L/

with /a/, /´/ with /e/,

and /I/ with /i/. This

is also somewhat the predicted problems from the contrastive analysis.

The major suprasegmental feature noticed from the outset of the tutoring sessions

was an absence of contracting to make reduced forms of some very common English

words. My subject usually and very clearly articulated every final /h/

sound instead of reducing it to /n/ as is common

in American English. I believe that this articulation resulted in his tendency

to make a distinction between words that are commonly reduced in American English.

These are usually words ending in “ing” followed by “to”

such as “going to”, “have to”, and “want to”.

To help my subject practice improving his problems with certain consonant phonemes,

I gave him minimal pair drills at each tutoring session. Afterwards, I had him

listen and repeat after me. With regards to vowel phonemes, I did not use minimal

pairs because I felt that reading words with the vowels in question would not

be very helpful to him and may cause more problems due to the unpredictable

nature of vowels in the English orthographic system. Therefore, I had my subject

listen to my voice, watch my mouth, and repeat after me. This seemed to work

initially, but I doubt his improvement without continued practice. To help improve

his linking to form contractions, I gave him a list of common words that are

reduced. We practiced both the original words and the target form. Then I would

tell him to think about those words during our free-talk time. When I used those

words in my own speech, I tried to add slight emphasis to highlight the form

to him. Again, this seemed to work at first, but without continued practice

I am concerned about his improvement.

RESULTS/ CONCLUSION

Throughout the brief duration of this tutoring project, it was difficult to

hear any obvious improvements in my subject’s pronunciation. It is possible

that one-month is too short of a time span to find a clear improvement in a

person’s phonology. However, by comparing my notes from the initial assessments

in the areas that I looked at with a final assessment made during our last tutoring

session, it seemed that he made slight improvement in his linking to form contractions

(gonna, hafta, wanna) and in some correct target forms (initial /se,si/, /wo/,

/l/-/®/ distinction)

which resulted from a perceived increase in false-starts and repetitions. These

examples seemed very random.

Perhaps his slight improvement in linking was due to the fact that we focused

on this suprasegmental feature the most. Although he still said examples like

“going to” and “want to”, I detected an increase in his

natural use of the reduced forms “gonna” and “wanna”. Hopefully

his awareness will help him further achieve the target-like speech for these

forms.

With regards to some of his improvements at the phonemic level, I perceived

that he made more false-starts and repetitions of his own speech at the end

of our tutoring sessions which resulted in correct forms being used some of

the time. I say perceived because I did not really have a measure of this from

the beginning; during initial assessments I did not think to look for false-starts

and repetitions. However, it is possible that an increase in these strategies

was the result of his increased awareness of producing the correct form. For

example, when talking about going to travel in the mainland, he first said something

about, “She-ah,” then stopped and began again by producing, “Seattle”

which he repeated again immediately. He did not always use these two strategies

together, but this was the most notable example. Even with his false-starts,

sometimes he still make mistakes.

In retrospect, I have found this entire project to be very worthwhile for myself

and probably for my tutoring subject as well. As a tutor and future teacher

of ESL, I believe that it is important to know the value of contrastive analysis

and how it can be applied practically. This is especially true since my project

has focused on a native Japanese speaker learning English; in the future I expect

my teaching career to also focus on this language group. Though this project

I have learned very useful information regarding possible phonological errors

of Japanese speakers of English and have applied this information in the real

world.

According to my subject, learning about the problem areas of his pronunciation

has made him more aware when he speaks and when he listens to others. He told

me that now when talking with a friend, teacher, or other native English speaker,

he can hear his “voice in his head” more because he pays attention

to how he and others are speaking. Instead of just trying to listen to the words

as a whole and then trying to decipher their meaning, he now also tries to listen

to the phonological features of the words that he hears. He believes that this

is helping him pronounce his own words better.

My subject seemed to like individual pronunciation tutoring very much. Our previous

tutoring sessions were limited to conversation and working on his language-school

homework. At that time I did not have the knowledge of phonology to constructively

help him with his pronunciation. He told me that he liked the pronunciation

tutoring because he did not receive pronunciation teaching either in his Japanese

schooling or at his language school.

In reality, it is difficult to think of any shortcomings of individual tutoring

as a way to improve pronunciation. This kind of tutoring seems to be very useful

to both tutor and tutee, my subject seemed to appreciate and enjoy pronunciation

exercises, and individual tutoring as opposed to classroom teaching allows for

a greater concentration of time and attention on specific problem areas. My

experience with individual pronunciation tutoring has been very positive; however,

I would think that the major weaknesses in this approach would be if a tutor

lacks the knowledge and skills to tutor in this manner and/ or if the student

had no motivation to improve. Thankfully, a determined tutor can learn the skills,

but student motivation is a subject best left for psycholinguists to consider.

In conclusion, a contrastive analysis of two languages can be very useful for

tutoring certain phonological aspects of the target language that may be found

to be problem areas for both speakers and listeners. A contrastive analysis

may be of valuable assistance to both the tutor and to the tutee by creating

awareness of possible problem areas. This awareness can allow for specific and

intensive assistance to improve pronunciation. Although progress may take quite

some time and a great deal of effort, I feel that creating awareness of the

problem is the necessary first step towards phonological improvement.

Bibliography

Allott, Robin. Japanese and the motor theory of language. Available online

at: members.aol.com/rmallott2/Japanese.htm#phon

Fromkin, Victoria and Robert Rodman. 1998. An introduction to language.

Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace College Publishers.

Han, Mieko Shimizu. 1962. Japanese phonology: an analysis based upon sound

spectrograms. Tokyo: Kenkyusha Press.

Kitao, Kenji. "Contrastive analysis between English diphthongs [ai], [au],

and [øi], and similar vowel combinations in Japanese". In K. Kitao

and S.K. Kitao, English teaching: theory research, and practice,124-135.

Kitao, Kenji. 1995. "Difficulty in English pronunciation for Japanese people".

In K. Kitao and S.K. Kitao, English teaching: theory, research, and practice,137-151.

Kohmoto, S. 1969. New English phonology. Tokyo: Nan'un-do.

Ladefoged, Peter. 2001. A course in phonetics. Orlando, FL: Harcourt

College Publishers.

Vance, Timothy J. 1987. An introduction to Japanese phonology. Albany,

NY: State University of New York Press.

TOP BACK HOME

contents (c) 2001 Shawn Ford/ Webb-Ed

Press

sford@hawaii.edu