Enhancing Wireless Physcial-Layer Key Exchange (iJam) with Channel Randomization

EEx96, Fall, 2020

Executive Summary

Wireless physical layer security scheme, such as orthogonal blinding, is able to achieve this level of secure communications by transmitting artificial noise into the null-space of the receiver’s channel, thus corrupting reception of any unwanted eavesdroppers. This physical-layering method supersedes other theoretical methods, such as zero-forcing beam-forming because it does not rely on having any prior knowledge about an eavesdroppers channel. Security based analysis supports the idea that Orthogonal blinding can closely approach the same secrecy rate as zero-force beam-forming when compared to single-antenna eavesdroppers. However, further analysis shows that orthogonal blinding is less effective against multi-antenna eavesdroppers. This is because multi-antenna eavesdroppers would have sufficient spatial dimensions to aid them in separating the original message from the artificial generated noise. Schulz and Zheng et al. demonstrates that an eavesdropper can leverage a known or low entropy symbols in a transmission and quickly create a decoding filter in order to recover the missing pieces of the transmission; equivalent to a known-plaintext attack in crypto-analysis. In this project, we investigate an orthogonal blinding based physical-layer security method immune to the known-plaintext attack.

Presentation

Highlights

Logistics

- CRN

Semester EE196 EE296 EE396 EE496 Fall 2020 76253 76254 76255 76256

Introduction

When performing RF communication between a transmitter and receiver, the signal observes a channel effect, which is dependent on many factors, such as scattering, fading, and power decay as the distance increases. This means the signal sent by the transmitter will not be the signal received by the receiver. However, it is possible to undo this channel effect on the signal with the use of pilot symbols. By utilizing a universal truth where everyone knows what value the pilot symbols are and their position in the message, we can calculate the channel effect by dividing the received pilot symbols by the original pilot symbols, and using this value to remove the channel effect on our received signal.

RF communication is unsecure however, as the tranmission is unencrypted and can easily be seen by an eavesdropper. To establish an encrypted communications channel, iJam, a key exchange protocol, was introduced such that a key can be exchanged over the RF channel. The iJam protocol requires the transmitter, Alice, to send each key symbol twice. The receiver, Bob, equipped with a second transmitting antenna, will randomly choose which key symbol to jam with his second antenna. Since Bob knows which of the two key symbols is being jammed, he can pick out the unjammed symbol, then reconstruct the key by accumulating the unjammed symbols. From an Eavesdropper, Eve’s point of view, she is unsure which of the pair of key symbols is the jammed symbol and which is not, leading to a 50% chance of guessing which symbol is correct, effectively obscuring the key from others.

The downfall to iJam is that it only works against single-antenna eavesdropper. With a multi-antenna setup, an eavesdropper can use the additional spatial diversity, the pilot symbols used to calculate the channel effect, and the unchanging channel between the legitimate transmitter and itself to equalize the channel between itself and the transmitter determine which of the two symbols is being jammed, therefore picking out the unjammed symbols and reconstructing the key.

This is where we propose a defense mechanism against multi-antenna eavesdropper, iJam with channel randomization. This builds off of iJam and comes in two parts: precode the channel effect that we expect to see between the Alice and Bob, removing the need for pilot symbols, and to constantly rotate the transmitting antenna to create a constantly changing channel. In order to precode the channel effect, we develop a training model, or a angle-of-departure (AoD) estimation algorithm, to predict the channel effect, which is effective in a unchanging environment. Since we precode the channel effect on Alice’s side, the receiving signal that Bob sees requires no further processing, and no longer needs pilot symbols to undo the channel effect. Since there are no longer any pilot symbols in the transmission, an eavesdropper can no longer calculate the channel effect between itself and Alice, thus unable to decipher the key symbols. As for the second part, we constantly rotate Alice’s antenna, which in turn constantly changes the channel. In conjunction with the first part, our AoD estimation algorithm will be trained with the angles that we will use as we rotate, so we have a wide range of channels to use. We do this since in contrast, had we kept a constant channel by not rotating the antenna, an eavesdropper with enough time can decipher the channel effect and recover the key. By constantly changing the channel, an eavesdropper is unable to keep up and cannot determine the channel effect, securing the key transmission.

Background

iJam as discussed has its limitations as to what adversaries it can keep information from, in this case multiple eavesdroppers. The core of iJam relies on two key components, keeping the jammed and unjammed portions of the signal unknown by a signal eavesdropper, and being certain that the jamming is not too strong or too weak so that a eavesdropper would be able to guess the clean signal. The first task is done by utilizing OFDM signals, and when the transmissions are instead gaussian in nature as opposed to a QAM or BPSK signal which has a clear distinction of what is being sent, the applied gaussian noise will act as the perfect jammer. A gaussian noise added on top of a gaussian signal, under the central limit theorem, combining all the pulses within the OFDM signal will have a gaussian distribution. In the eyes of the eavesdropper, it would be unable to differentiate which parts of the transmission have been jammed, but to the receiver which has been actively sending out gaussian signals knows when to process the signals that have not been jammed. The unpredictable part with this method of encryption is if an eavesdropper is placed in an area where the receiver’s jamming is too close or too far from it. By being too close to the jamming, the eavesdropper would be able to see that there are certain parts of the signal that have increased jamming power, and would be able to take a better educated guess at whether it is being jammed or not. By being too close to the receiver, jamming power would be too low and just like with jamming power being too high increases the chances that the eavesdropper would be able to determine the unjammed signal. To counter this problem with jamming strength, iJam would have the receiver jam at varying power levels to throw off the eavesdropper.

If there were two eavesdroppers instead of just the one, as iJam anticipates, then the second eavesdropper would be able to get another reading on the jamming power. With the second dataset the chances that it would be able to determine the clean signal increases when comparing the two eavesdropped signals and it sees the differences. To counter this, channel randomization is applied instead of alternating jamming power. The signal that is transmitted is not only affected by the jamming that occurs, but there are other factors that are difficult to control such as scattering, fading, power decay, and multipath. Taking advantage of this, an improved layer of security is used with iJam. This layer is called channel randomization, by using a rotating transmitter and the constantly changing angle of departure from Alice, we can assure that even with multiple eavesdroppers there will not be leakage of the key. This is done through a testing phase between Alice and Bob. Throughout Alice’s rotation the channel state information is constantly changing and the exact stream of data that Bob is receiving would be different from the sent. By taking the received information and comparing it to the sent signal and angle of departure, the full channel effect can be found. As Alice and Bob now know the channel effect, the obfuscated signal caused by the rotation can be cleared. Combine this with what iJam can do, you now have a system that has a way of securing RF communication.

Methodology

To predict the CSI for different antenna modes without sending the pilot symbols, Alice (TX) computes the angle of departure vector (AoD) using a subset of antenna modes dedicated for training. This can be modeled as follows:

$$\mathbf Y = \mathbf H\mathbf X + \mathbf N$$

where $\mathbf Y$ is the signals received by Bob, $\mathbf H$ is the channel state information (CSI), $\mathbf X$ is the transmitted signal Alice trasmits, and $\mathbf N$ is the channel noise. The channel noise is an additive white Gaussian distributed noise representing the random processes that occur in nature.

$\mathbf H$ can be modeled as the inner product between the area of departure (AoD) vector, $\mathbf h$, and the transmitter’s (TX) antenna pattern, $a$. This can be represented in the following equation:

$$\mathbf H = \sum \mathbf a\mathbf h$$

Each element in the AoD vector $\mathbf h$ represents the environment’s attentuation effect on the TX signal in a specific direction. Within a short period of time, these elements do not change.

To further analyze the attenuation effects, the charactistics of the AoD vector $\mathbf h$ can be broken down into two components: a magnitude and phase. This can be modeled as follows:

$$\mathbf h = |\mathbf h|e^{-\theta}$$

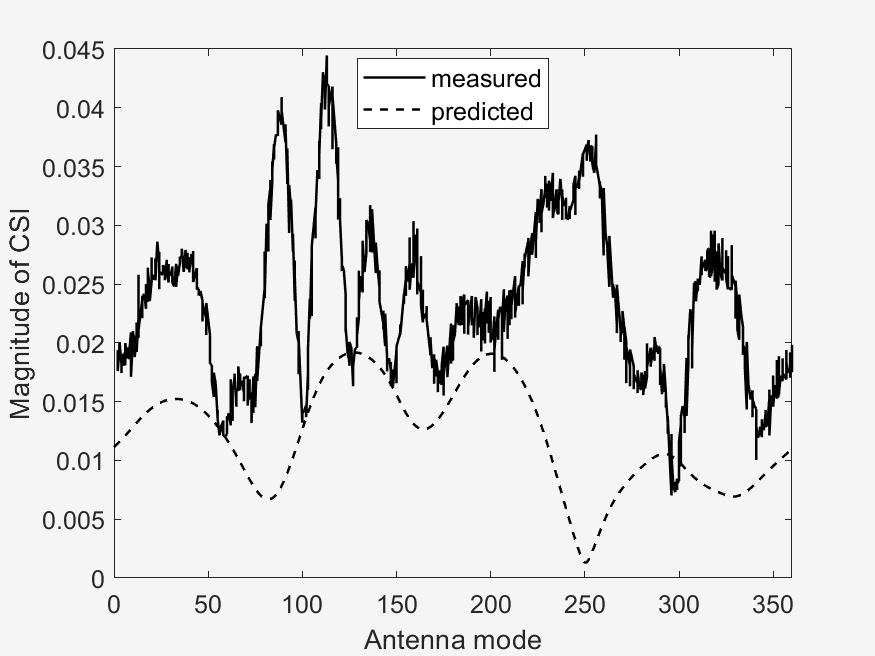

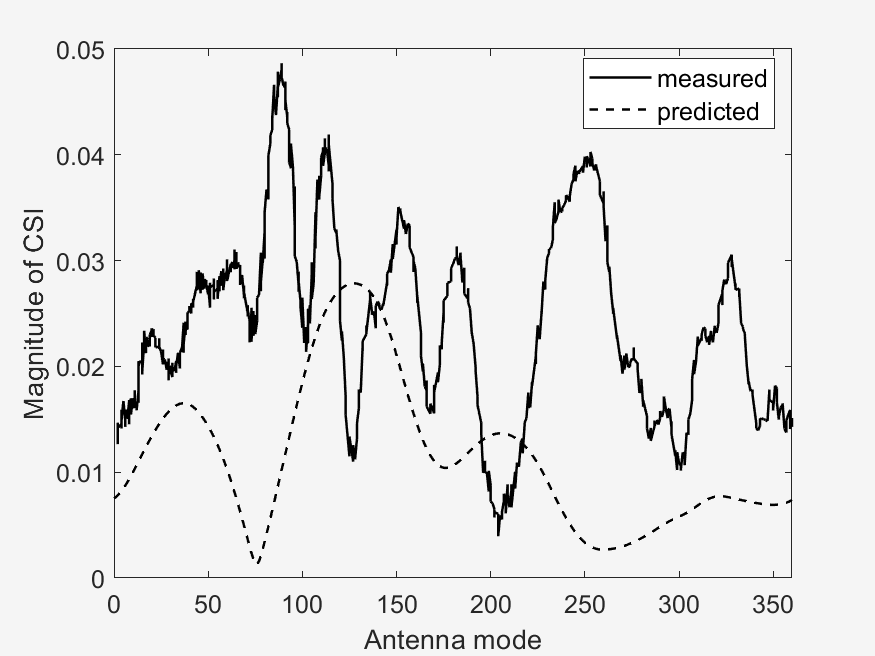

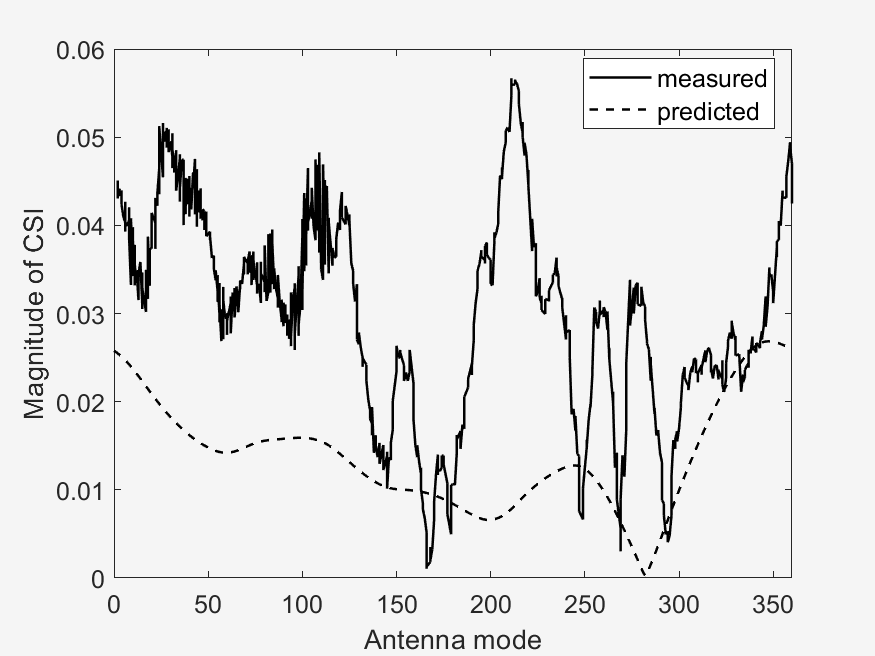

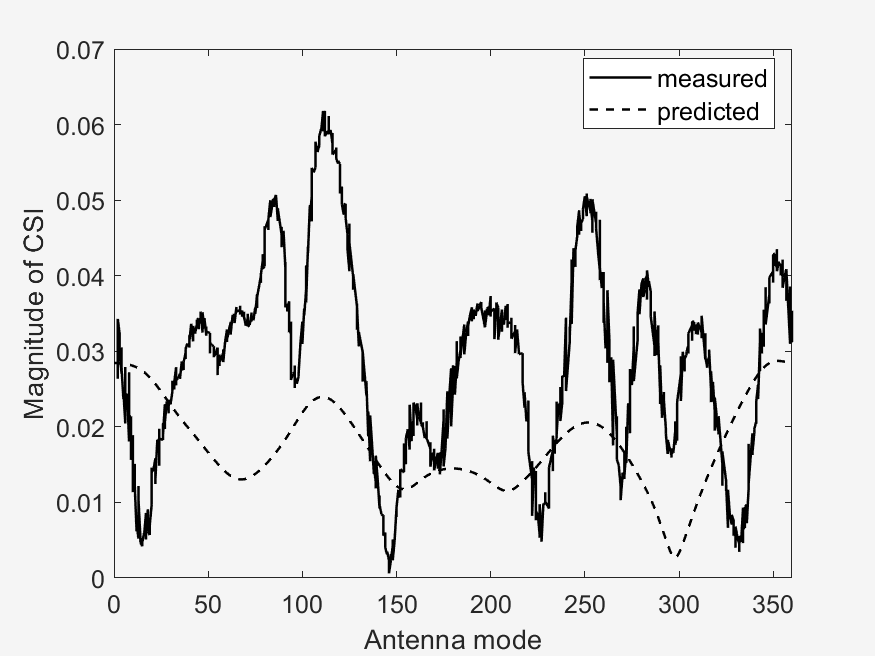

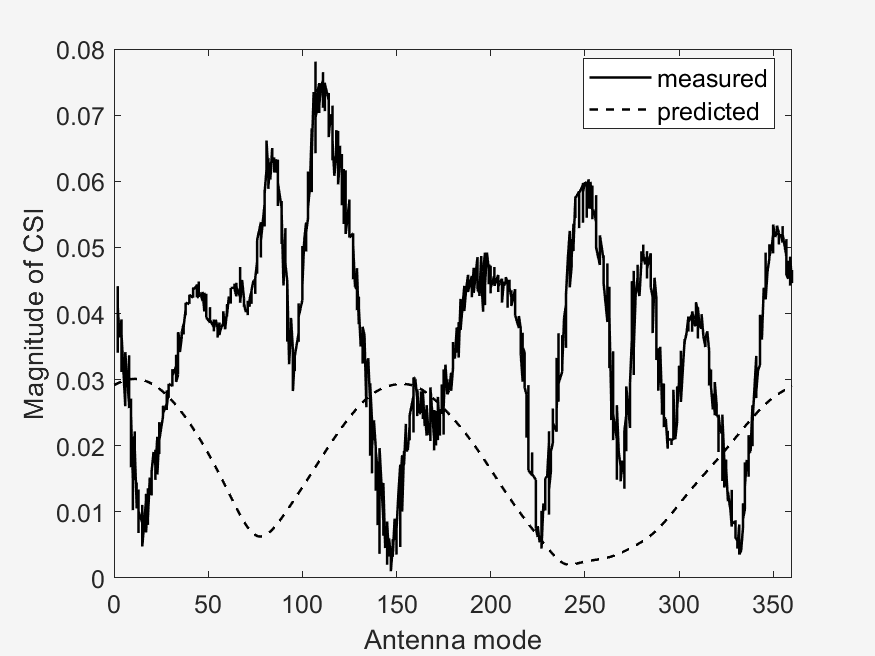

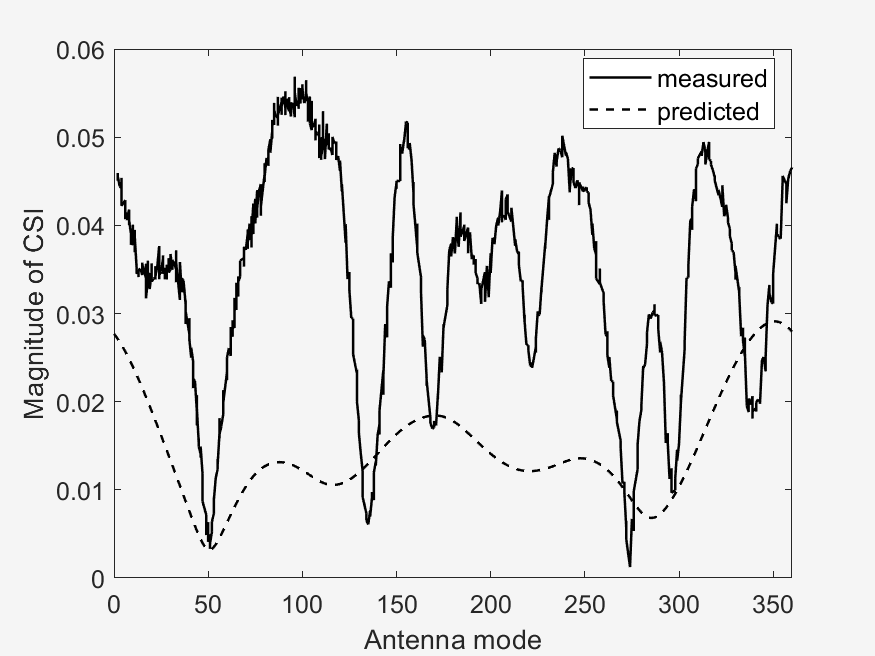

where $|\mathbf h|$ is the magnitude of the AoD vector and $\theta$ is the phase of the vector. As the signal travels further (i.e. RX is farther from the TX), the magnitude of the transmission decreases. The phase, too, depends on the distance the RX is from the TX. Keeping magnitude constant, the phase will change the transmission pattern every wavelength of the signal. Combining the two characteristics together, we observe a pattern similar to the one in Figure 1 below.

To solve the CSI model, the MUSIC (Multiple Signal Classification) algorithm is used to compute the AoD vector. This algorithm minimizes the difference between the estimation and ground truth CSI. A regular MUSIC algorithm requires Alice to measure the CSI with a sufficient number of antenna modes during the training phase in order to solve for the AoD. However, this significantly limits the number of available antenna modes for data transmission.

To reduce the number of antenna modes used during training, and consequently increasing the number of antenna modes for data transmission, the problem is converted into a regularized underdetermined LP with less equations than the unknowns. This problem is then solved with a compressive sensing technique.

With the computed AoD, Alice will be able to predict $\mathbf H$ during transmission and sends the product of the inverse of $\mathbf H$ multiplied to $\mathbf X$ in order to pre-equalize the channel for Bob.

By itself, this model is vulnerable to eavesdropping from an adversary (Eve) with multi-antennas. With multiple antennas, the eavesdropper will be able to generate more than one channel models, increasing their spacial diversity. Providing more degrees of freedom will enable Eve to determine which bits of the transmission are being jammed through iJam. Thus, the idea to introduce channel randomization to along with iJam was conceived.

Implementation and Experimentation

iJam with Channel Randomization was implemented by connecting various hardware components with Labview, which allows us to interface with each hardware component in order to perform our experiments. The implementation and experimentation we will be going over in detail with be of the 09/10/2020 experiment.

The hardware used in this experiment are two high gain directional antennas (PE51082) for Bob and Eve, a rotating antenna (WAT5VJB) for Alice, a planar RF reflector, as well as USRPs (Ettus N210) for each antenna to generate and receive signals. In Labview, we are able to have Alice transmit either a randomized bitstream or a bitstream with all ones, and we can then view the received signal at both Bob’s and Eve’s end. Channel randomization can then be toggled, by taking the channel effect at the receiver side, and precoding it to Alice’s signal. As an angle of departure algorithm has not yet been implemented, a temporary solution is used where we take the channel state information at the receiver and use that to precode the message.

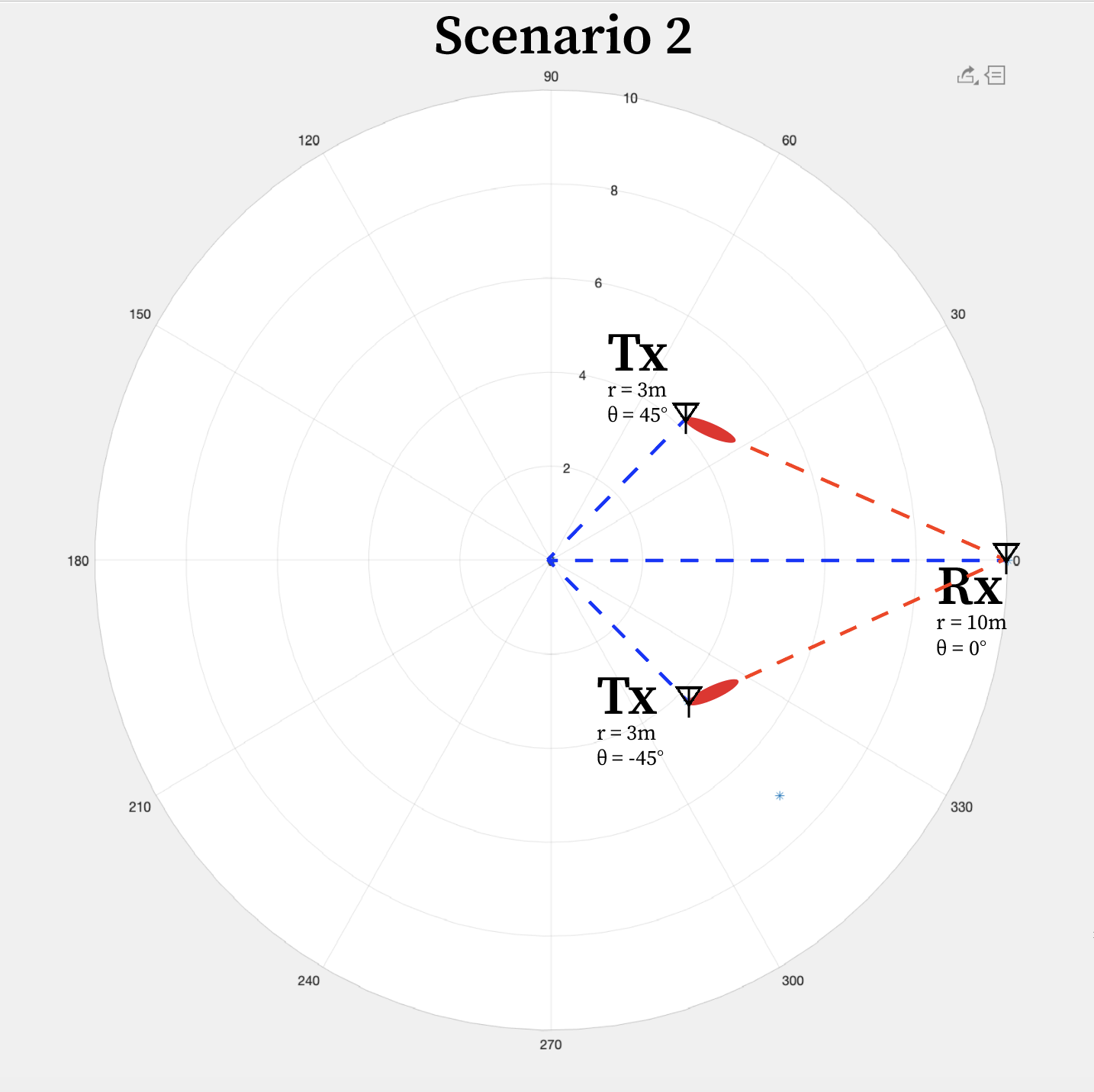

In the 09/10 experimentation, we ran with three scenarios. These scenarios are modeled in the following figures.

The various scenarios were picked in order to determine whether we can view the reflected signal path clearly when running the experiment, in order to verify that we are processing/receiving the signal correctly. Along with this, the scenario allows us to determine what Eve, the eavesdropper, sees when receiving the signal from Alice. We ran the experiment outdoors in as an open space as possible, to try and minimize signal reflection. It can be seen however, that in the experiment pictures there are buildings in the vicinity when running the experiment.

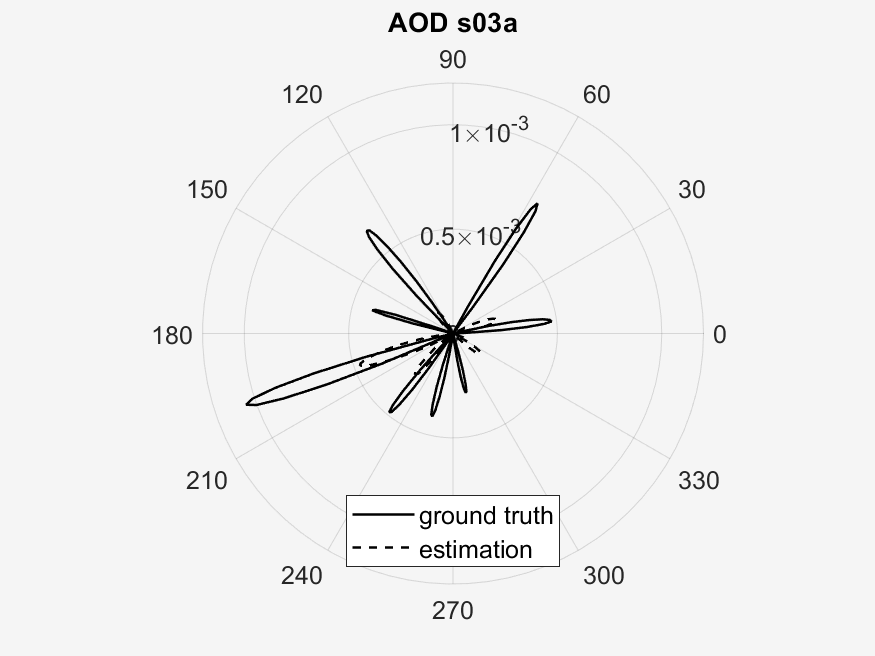

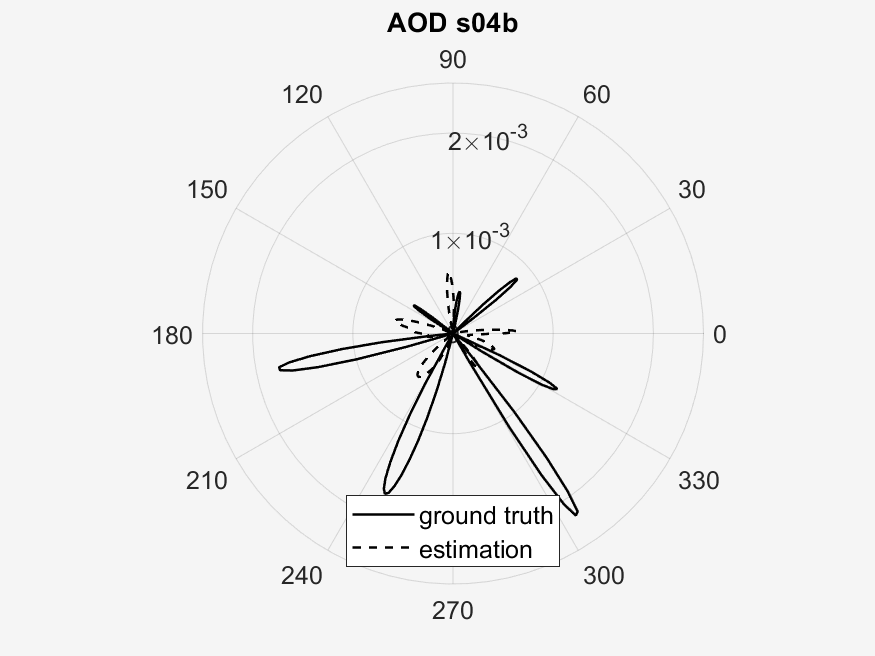

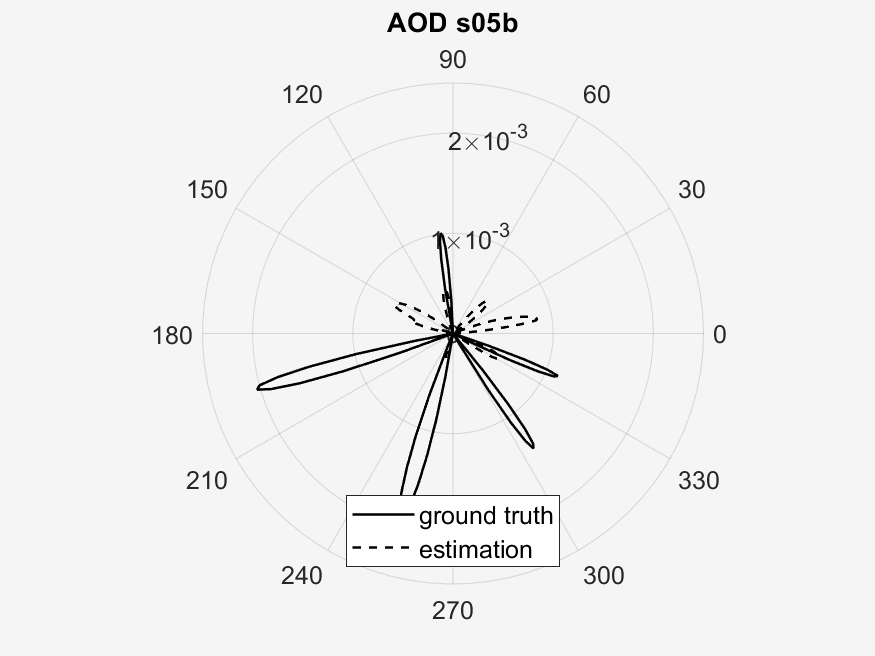

The results of the experimentation can be seen in the following image galleries.

The important points to look at in these results is the measured vs predicted channel state information magnitude (CSI). It can be seen that the measured CSI magnitudes correlates loosely with the predicted CSI magnitudes. This may be due to errors in the prediction method used or an unstable phase of the data. Then another point of interest is that of the ground truth vs estimated AoD vectors. In the circular plots it can be seen that for the scenarios with a higher RPM, that the estimated AoD vectors correlate less closely to the ground truth as compared to scenarios with a lower RPM. Then again with the difference that RPM makes, is that in sub scenarios with the same RPM (a & b), the measured CSI magnitude are similar to each other, whereas the one sub scenario (c) with a different, faster RPM, is visually different from the two other sub scenarios. This furthers our analysis in the difference of faster RPMs in the implementation of our algorithm, where faster RPMs, where they may provide a faster key transmission speed may have a lower stability.

Conclusion

iJam with Channel Randomization successfully achieves to protect key bits from multi-antenna eavesdroppers by creating an artificially fast-fading channel effect. This work demonstrates an improved approach to the existing iJam method who utilizes a jamming method to randomly jam one of two duplicated bits. However, iJam is found to be vulnerable to multi-antenna eavesdroppers who can utilize the spatial diversity to calculate the channel effect of the pilot symbols. Therefore, we propose a defense mechanism against such attacks by combining a channel randomization with a prediction-based channel equalization.

The channel randomization technique leverages a mechanically reconfigurable antenna that rotates to rapidly change the channel state information during transmission. The angle-of-departure (AoD) based channel estimation is used to cancel its effects for the intended receiver, and the pilot vulnerability exploited by an eavesdropper is now eliminated with our CSI channel estimation mechanism, which this allows Alice to predict and pre-equalize the channel effect for Bob. As a result, a secure establishment is created between the transmitter and receiver, while the eavesdropper views an unstable channel.

Appendix

Equipment

- Alice

- USRP node: Ettus N210

- Antenna(s)[decimeter band]: WAT5VJB log-periodic (850-6500 MHz)

- Antenna(s)[mmWave band]: TMYTEK BBox Lite (24000 - 30000 MHz)

- Bob

- USRP node: Ettus N210

- Antenna(s)[decimeter band): WAT5VJB or PE51082 (2400 MHz only)

- Antenna(s)[mmWave band]: TMYTEK BBox Lite (24000 - 30000 MHz)

- Eve

- USRP node: Ettus N210

- Antenna(s)[decimeter band): WAT5VJB or PE51082 (2400 MHz only)

- Antenna(s)[mmWave band]: TMYTEK BBox Lite (24000 - 30000 MHz)

- RF reflector

- Large corner, small corner, plane reflector.

Data

Exp. 2020/01/23

| Scenario | Alice Gain1 | Bob Gain | Eve Gain | Central Frequency (Hz) | I/Q Rate | Reflector | Rot. Speed (rpm)2 | Time (s) | Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 30dB | 0dB | 0dB | 1.6G | 500k | Corner (lg) | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 01 | 45dB | 0dB | 0dB | 1.6G | 500k | Corner (lg) | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 01 | 60dB | 0dB | 0dB | 1.6G | 500k | Corner (lg) | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 01 | 30dB | 0dB | 0dB | 2.6G | 500k | Corner (lg) | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 01 | 45dB | 0dB | 0dB | 2.6G | 500k | Corner (lg) | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 01 | 60dB | 0dB | 0dB | 2.6G | 500k | Corner (lg) | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 01 | 45dB | 0dB | 0dB | 3.6G | 500k | Corner (lg) | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 01 | 60dB | 0dB | 0dB | 3.6G | 500k | Corner (lg) | 3 | 100 | Download |

Exp. 2020/01/30

| Scenario | Alice Gain | Bob Gain | Eve Gain | Central Frequency (Hz) | I/Q Rate | Reflector | Rot. Speed (rpm) | Time (s) | Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 02 | 30dB | 0dB | 0dB | 0.9G | 500k | Corner (lg) | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 02 | 45dB | 0dB | 0dB | 0.9G | 500k | Corner (lg) | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 02 | 30dB | 0dB | 0dB | 1.6G | 500k | Corner (lg) | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 02 | 45dB | 0dB | 0dB | 1.6G | 500k | Corner (lg) | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 02 | 30dB | 0dB | 0dB | 2.6G | 500k | Corner (lg) | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 02 | 45dB | 0dB | 0dB | 2.6G | 500k | Corner (lg) | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 02 | 30dB | 0dB | 0dB | 3.6G | 500k | Corner (lg) | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 02 | 45dB | 0dB | 0dB | 3.6G | 500k | Corner (lg) | 3 | 100 | Download |

Exp. 2020/03/05

| Scenario | Alice Gain | Bob Gain | Eve Gain | Central Frequency (Hz) | I/Q Rate | Reflector | Rot. Speed (rpm) | Time (s) | Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 02 | 30dB | 0dB | 0dB | 1.6G | 500k | Corner (sl) | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 02 | 30dB | 0dB | 0dB | 1.6G | 500k | Corner (lg) | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 02 | 45dB | 0dB | 0dB | 2.6G | 500k | Corner (sl) | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 02 | 45dB | 0dB | 0dB | 2.6G | 500k | Corner (lg) | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 02 | 60dB | 0dB | 0dB | 3.6G | 500k | Corner (sl) | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 02 | 60dB | 0dB | 0dB | 3.6G | 500k | Corner (lg) | 3 | 100 | Download |

Exp. 2020/09/10

| Scenario | Alice Gain | Bob Gain | Eve Gain | Central Frequency (Hz) | I/Q Rate | Reflector | Rot. Speed (rpm) | Time (s) | Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 03 | 15dB | 0dB | NA | 2.4G | 500k | NA | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 03 | 30dB | 0dB | NA | 2.4G | 500k | NA | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 03 | 30dB | 0dB | NA | 2.4G | 500k | NA | 1 | 100 | Download |

| 04 | 15dB | 0dB | NA | 2.4G | 500k | NA | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 04 | 30dB | 0dB | NA | 2.4G | 500k | NA | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 04 | 30dB | 0dB | NA | 2.4G | 500k | NA | 1 | 100 | Download |

| 05 | 15dB | 0dB | NA | 2.4G | 500k | Plane | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 05 | 30dB | 0dB | NA | 2.4G | 500k | Plane | 3 | 100 | Download |

| 05 | 30dB | 0dB | NA | 2.4G | 500k | Plane | 1 | 100 | Download |

Acknowledgement

This project is partially supported NSF grants CNS-1948568, DGE-1662487, and TMYTEK mmWave research initiative.

-

The rotating speed is based on actual measurment instead of the input value to the rotator interface. For instance, the actual rotating speed is 3rpm when the input value is 10rpm. ↩︎

-

The gain range of the SBX daughter board used by the experiment is 0.0 to 31.5 dB step 0.5dB. Therefore, to set the gain to 9dB in Labview, the gain step should be 18. The WAT5VJB LPA gives approxmiately 10 dBi gain in its boom diretion. [data url]: # (data urls) ↩︎