Lower Mekong Archaeological Project (LOMAP)

LOMAP Web Galleries

Conde Nast Traveler article on "Cambodia's Undiscovered Temples" [PDF] featuring LOMAP site (August 2012)

Shawn Fehrenbach "Cambodia Down South: Images of an Archaeological Field Season in the Delta" [PDF] (August 2010)

LOMAP Co-Directors:

Dr. Miriam T. Stark, Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Hawai’i-Manoa ,USA

H.E. Chuch Phoeurn, Secretary of State, Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts, Kingdom of Cambodia

Cambodia is a country rich in cultural heritage, and its crown jewel of Angkor Wat represents only one part of a deep and varied archaeological record. Its archaeological tradition was begun in the mid- to late 19th century, as the French explored the Mekong and Angkor Wat regions. At its peak, the ancient Khmer Empire dominated substantial portions of continental Southeast Asia, and studying its developmental trajectory is imperative to comparative research on early state formation. Archaeological work in Cambodia is thus fuelled by both ethical and intellectual imperatives.

This web page provides an introduction to goals and research objectives of the Lower Mekong Archaeological Project, which has focused on southern Cambodia since 1996. We first provide a brief introduction to the research rationale that structures this project, then discuss the project’s interrelated focus on research and training, and then summarize some of the project’s findings. Readers are encouraged to consult the following URL, which contains project publications in pdf format:

<http://www.anthropology.hawaii.edu/People/Faculty/Stark/index.html#sbibliography>

Why Southern Cambodia and the Mekong Delta?

The earliest states in mainland Southeast Asia emerged between 500 B.C. and A.D. 500. Regrettably, it is precisely this period that forms a temporal and disciplinary gap in our knowledge: it covers between the end of most archaeologists’ period of interest, and before the appearance of inscriptions and statuary that historians and art historians study. Systematic analysis of trade goods like beads suggests that participation in a South China Sea maritime trade network began in the late centuries BC for settlements that emerged along the coasts and inland deltas of mainland Southeast Asia. By the early centuries AD, several coastal regions may have housed city-states. That these polities were integrated in some ideological (if not political) respects seems evident from their corpus of shared material culture, although scholars continue to debate the catalyst behind this broad stylistic horizon and its political implications.

The early historic period (ca.500 B.C. - A.D. 500) was a kind of “axial age” for mainland Southeast Asia. Social, economic, and political transformations began during this period that culminated in the earliest states in the region. The polity historians call “Funan” developed in the Mekong delta during this time, and parallel developments to the north in central Vietnam produced the Cham civilization; still further north, in the Bac Bo region, was the fluorescence of the earliest Vietnamese state, in conflict with the Han Chinese. To the east in central Thailand, a polity that historians call “Dvaravati” emerged with characteristic art styles and quite likely moated settlements. In the Irawaddy river valley of today’s Myanmar, large walled Pyu settlements arose – and grew still larger – through the first millennium A.D.

Archaeologists working across Southeast Asia’s mainland have documented the nearly pan-regional character of these developments. From ca. 500 B.C. - A.D. 500, a recurrent settlement pattern characterizes most of mainland Southeast Asia: (1) the appearance of moated, fortified settlements associated with water control features; (2) the development of a settlement pattern with a primate center and its surrounding satellite settlements; and (3) the recovery of a similar range of nonlocal goods, such as ceramics, metals, and glass. If Chinese documentary records provide reliable chronological information for the region then what we may see in the latter half of the first millennium A.D. is a pattern of cycling in political centers across the river valleys and deltas of mainland Southeast Asia.

Nowhere is this process more pronounced than in the Mekong delta that is now southern Cambodia and southern Vietnam. Called Funan or “Funanguo” by visiting Chinese dignitaries in the 3rd century A.D., the delta and coastal-based polity or kuo (Chinese for country or state) reputedly contained elites described as “kings” with whom the Chinese undertook tribute transactions for several centuries. Documentary evidence suggests that the delta also housed multiple urban centers between the 1st-6th centuries A.D.

A growing body of archaeological evidence suggests that regions like the Mekong delta housed states by the early first millennium AD. French interest in southern Indochina’s Khmer art and architecture drew many famous scholars to the region, including art historians and historians during the early 20th century. The first archaeological investigations were undertaken during World War II, when Louis Malleret supervised excavations at the looted but informative site of Oc Eo and investigated archaeological sites in area surrounding this site. International and civil war precluded additional archaeological research in the region until the late 1970s, when Vietnamese archaeologists resumed excavations at “Oc Eo Culture” sites throughout the delta. Since then, perhaps as many as 150 such sites have been documented, and French-Vietnamese collaborative research Oc Eo has been extremely important. Findings from this archaeological work suggest that large populations lived, constructed stone statuary and brick monuments, and inscribed stelae in several areas of the delta during the first millennium A.D.

What kinds of urban configurations did these settlements assume? What was the structural nature of these polities? The nature of change that led to these developments remains largely undertheorized. Some of the better theorized models derive from island Southeast Asia, emphasize cycles of expansion and collapse that characterized early Southeast Asian political formations, and focus on the movement of prestige goods and other symbols of power in connection with the region’s increasing participation in maritime trade networks. Yet few archaeologists working in mainland Southeast Asia have systematically explored historical organizational models to characterize the period between 500 BC – AD 500 that include (but are not limited to) the 19th century theater state model from Clifford Geertz, Stanley Tambiah’s galactic polity model based in 13th-14th century Thailand, and O. W. Wolters’ “mandala” model during the late first millennium BC and early first millennium AD. Much more empirically-based systematic archaeological research is needed on this period of time, and across much of mainland Southeast Asia, to begin answering these questions.

Research and Training through the Lower Mekong Archaeological Project

Cambodia’s recent and tragic history has largely human dimensions that many historians and scholars have detailed. But the fact that this country also has one of the most spectacular archaeological records of ancient states in Southeast Asia is also important. Archaeological sites throughout Cambodia have fascinated the western world from the late 19th century, and French archaeologists continued to study and restore prehistoric and historic period sites in Cambodia until the early 1970s. That heritage practitioners across Southeast Asia also appreciated Cambodia’s rich archaeological record is clear by a decision in by the Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization (SEAMEO) to host the 8th Council Conference in Phnom Penh in December 1972. At this conference, the region’s specialists met to develop plans for ARCAFA (SEAMEO Applied Research Centre for Archaeology and Fine Arts), which would be based in Phnom Penh. Soon thereafter, Cambodia collapsed into a long civil war that terminated most archaeological research and historic preservation activities, and took countless lives. ARCAFA took six more years to become established in Bangkok as SPAFA (the Regional Centre for Archaeology and Fine Arts), and has since become the leading Southeast Asian organization for training in archaeological techniques and heritage management.

Cambodia’s intellectual was decimated, and the country’s archaeological community almost disappeared completely. Cold War geopolitics from the 1970s-1990s also precluded field research on ancient Khmer states and their predecessors, and world archaeology has suffered as a result. One outcome of the political turmoil between 1970 and 1989 was the disintegration of Cambodia’s archaeological heritage management system; another was the subsequent desecration of archaeological sites as they have been looted for the illicit antiquities trade. In the relative calm since the early 1990s, restoration and conservation of the Angkorian monuments of the Siem Riep province have been undertaken by the World Monument's Heritage Fund and UNESCO, involving specialists from Europe, Japan, the United States, and Southeast Asian nations. Although the situation is finally changing for the better, the continued lack of local expertise has led to the dominance of preservation work by foreigners rather than by Cambodians. The need to train the next generation of Cambodian archaeologists remains urgent.

Training Opportunities through Cambodian Archaeology

One of these programs was begun in 1994 by the East-West Center (co-director: Dr. Judy Ledgerwood) and the University of Hawai'i (co-director: Dr. P. Bion Griffin). That year, several institutions in the United States and Cambodia established an interdisciplinary, international research project that blends archaeology, art history, cultural anthropology, geography, and earth sciences. The University of Hawai'i/East-West Center/Royal University of Fine Arts Cambodia project represents collaboration between researchers at the University of Hawai'i (UH), the East-West Center (EWC), and the Royal University of Fine Arts (a division of the Ministry of Culture and the Fine Arts, or RUFA) in Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

The UH/EWC/RUFA Cambodia Project has been made possible to date by grants from the Indochina Initiative program (East-West Center), the UH-East West Center Collaborative Research Program, the East-West Center graduate fellowship program, the Asian Cultural Council, and the Henry Luce Foundation. The primary goal of the project's training component is to help rebuild the archaeology program in Cambodia by providing academic and field training to Cambodian students in the United States (at the University of Hawai'i and the East-West Center) and in Phnom Penh. Outstanding Cambodian students from the Royal Fine Arts University and the Ministry of Culture and the Fine Arts (Phnom Penh) receive training at the University of Hawai'i in English language competency, archaeology, and cultural anthropology.

Our project invests much of its training energies in training a new generation of archaeologists, both in Cambodia and elsewhere. One ultimate goal is to prepare Cambodian students to enter and complete an archaeology graduate program in either the United States or another country. Another important objective of the UH/EWC/RUFA Cambodia Project is to facilitate training and thesis research for non-Cambodian archaeology students. These students receive graduate training at the University of Hawai'i in archaeology, anthropology, and Khmer; special training in analytical techniques is also available for students with those interests. Graduate students participate in the Cambodian field project as field instructors and field researchers. The training component of the UH/EWC/RUFA Cambodia Project thus provides academic and field training to Cambodian students and American archaeology graduate students.

Research Opportunities through the Lower Mekong Archaeological Project

Training and research go hand in hand in the Lower Mekong Archaeological Project, which is co-directed by Dr. Miriam Stark (University of Hawai’i-Manoa, USA) and His Excellency Chuch Phoeurn (Secretary of State, Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts, Kingdom of Cambodia). This international, multi-disciplinary project currently involves American and Cambodian scholars with disciplinary interests in archaeology, geography, art history, historic preservation, and environmental studies. The Lower Mekong Archaeological Project (or LOMAP) was begun in 1996 to study aspects of early state formation in Cambodia's Mekong Delta.

This international collaborative archaeological project brings together scholars from several countries to investigate the early historic period of southern Cambodia. We undertake fieldwork in conjunction with field training for Cambodian students. Work to date has concentrated on archaeological sites in the Angkor Borei region (Takeo province, Cambodia) and at the site of Angkor Borei itself. Interestingly, the Khmer name "Angkor Borei" means "Ancient City"; short distance south of the town lies the hill of Phnom Da, on which the ancient Khmers built religious structures at different points in the past.

The town of Angkor Borei is a thriving center with a population of approximately 14,000. It has a small market, and many residential sections; below this modern town is the ancient site, and finding beads and larger artifacts is common as people garden and undertake household chores on their property. The farmland in Takeo is quite fertile, and many families in Angkor Borei farm. Angkor Borei also has an active trade network that moves goods across the Vietnamese border in either direction. The town has two major temples (vats), and a nearly continuous round of ceremonies and events that bring together families and build the community.

Our excavations have taken place in people's backyards and in their orchards, often with large local audiences. Archaeological research at the ancient site of Angkor Borei shows that the Khmer empire of the 9th-14th centuries represents only the endpoint in a deep historical record, whose origins lie south in the Mekong Delta. Southern Cambodia contains a rich yet poorly understood record of early historic period occupation, between ca. 400 B.C. and A.D. 500. Chinese travelers to this region in the third and sixth centuries A.D. described a kingdom of "Funan," with walled and moated cities that housed rulers, elites, and artisans of fine goods such as precious metals, jewelry, and other crafts (Article).

Archaeological work at contemporary sites in Vietnam suggests that this area was a thriving economic center in the trade routes that linked India to China by way of mainland Southeast Asia. The Mekong Delta was the `rice granary' of Asia, and Indian traders left their imprint on early historic period sites throughout mainland Southeast Asia during this time. The site of Angkor Borei is famous because the earliest dated Khmer inscription (dated to A.D. 611) in Southeast Asia was recovered from this site. In most areas of the world, the transition to history is associated with the appearance of writing. Indigenous writing first appeared in the early seventh century A.D. in southern Cambodia. Yet foreign accounts describe settlements in the lower Mekong region in the earlier centuries A.D., and suggest that the Mekong Delta housed some of the earliest states in mainland Southeast Asia several centuries before the advent of a written record. These polities (or states or mandalas) emerged during the early historic period, and are known solely through documentary evidence (Map).

LOMAP work began in 1996 with seed grants from the University of Hawai’i and the East-West Center Collaborative Research Program. Since then the project has been supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Geographic Society, and the Foundation for the Exploration and Research on Cultural Origins, the Center for Khmer Studies, and (most recently) the National Science Foundation. Our excavations in and around Angkor Borei have produced multiple series of radiocarbon dates that begin in the 4th century B.C. Previous dates for Angkor Borei, derived from inscriptional evidence, provide an early seventh century date, and sculptural analyses suggest a burst of activity during this time (Article).

These dates suggest a continuous occupational sequence from the fourth century B.C. to the seventh century A.D. Indeed, the fact that our radiocarbon dates derive from the first millennium B.C. may suggest that the settlement of Angkor Borei was occupied for centuries before the arrival of the Chinese emissaries to this region in the mid-third century A.D. LOMAP excavations, paleoenvironmental research, and archaeological survey all suggest that Angkor Borei was the central hub in a large network of early first-millennium sites across the northern Mekong delta, and that that much of the area between Angkor Borei and Oc Eo was densely populated during the first millennium A.D.

LOMAP Research: 1999 - 2003

LOMAP has undertaken four field seasons since 1999. Work in 1999 and 2000 concentrated on two goals: (1) excavating a portion of an early cemetery at the pagoda called Vat Komnou that dates between c. 200 B.C. - A.D. 200; and (2) launching a regional project of geoarchaeological research and paleoenvironmental reconstruction to understand human-environment interactions during the first millennium A.D.

The Vat Komnou Cemetery

Most of our attention focused on excavations at Angkor Borei (Article).Cambodia has been a Buddhist country for nearly two millennia, with a three-year break in the 1970s associated with the Khmer Rouge period. Nearly twenty years after the end of the Khmer Rouge era, Buddhist pagodas have been built or renovated throughout the countryside. Angkor Borei has two pagodas; one of them, Vat Komnou, lies on the south side of the river that bisects the settlement. On private land that flanks the southern boundary of this vat, a landowner began removing soil in 1998 to create new house lots for his children. His workmen encountered burials and the district governor halted his operations. We were invited to undertake systematic archaeological excavations in this area, and opened a test unit at the top of the slope. The upper layers of the unit contained construction fill, and we encountered portions of a cemetery approximately 3.5 meters into the matrix. These burials lacked clear grave cuts, and were often interred in close proximity to each other. In some cases, bodies in the lower strata lacked skeletal parts from what we believe were subsequent interments in the same location. Please consult Andy Brouwer's web site to obtain more details on the Vat Komnou excavations.

The 1999-20000 excavations produced portions of at least 80 primary and secondary burials, the latter involving commingled, partial individuals. As the largest skeletal sample from Cambodia recovered through systematic archaeological excavations, the Vat Komnou cemetery offers an invaluable opportunity to assess the relative health of Mekong Delta populations from 200 BC – AD 200. A preliminary skeletal analysis of the Vat Komnou cemetery was presented at the 2006 IPPA congress in Manila. Other research now in progress includes compositional studies of glass and carnelian beads recovered with the burials, technological, compositional and technological studies on the mortuary ceramic vessels (Article), and a zooarchaeological study of associated animal remains.

Our work constitutes the first archaeological excavation of that cultural layer at Angkor Borei, and the first systematic excavation of a cemetery of inhumations in Cambodian archaeology. Previous work at prehistoric sites like Samrong Sen and Mlu Prei recovered some human remains, but not large cemeteries. Radiocarbon dates from the University of Waikato Radiocarbon Dating lab suggest the cemetery was used between c. 200 B.C. and A.D. 200. Research on materials from the Vat Komnou cemetery hold great importance for reconstructing the early historic period in the Mekong delta. Previous work at Thai sites like Ban Don Ta Phet (by Ian Glover and his colleagues) provides material evidence for contact between South and Southeast Asia by c. 400 B.C. Yet the nature and intensity of this contact remains poorly understood. The fact that we found inhumations, rather than cremations, may suggest that inhabitants of this cemetery did not fully embrace the Indic ideology that may have already permeated the region. It may also be possible that the cemetery section we excavated did not include elite burials, and perhaps elites practiced different mortuary traditions at this time that incorporated Indic ideology.

Paleoenvironmental Studies through LOMAP: 1999-present

Dr. Paul Bishop (University of Glasgow) instigated the paleoenvironmental program in 1999, and focuses on both identifying and testing potential ancient canal segments and on reconstructing changing vegetational regimes in the region during the period of Angkor Borei’s political prominence. This work has now involved both paleoethnobotanical research by Dr. Dan Penny (University of Sydney) and luminescence work by Dr. David Sanderson (Scottish Universities Research and Reactor Centre, East Kilbride).

A critical element of the environmental research concerns identifying and dating canals that may have linked Angkor Borei (in the northern Mekong delta) and Oc Eo (in the southern Mekong delta)(Article 1, Article 2). Pierre Paris, a French geographer and colonial civil servant in Indochina, first observed these possibly ancient canals using aerial photographs in the 1920s and 1930s; however, he did not have the resources to ground-truth his claims. Geoarchaeological investigations, with Dr. Paul Bishop (University of Glasgow) in 1999. His analysis of aerial photographs identified a series of canals that radiate out from Angkor Borei to surrounding settlements, and some of these may correspond to the canals that Pierre Paris originally identified.

Results of this research have begun to suggest, among other things, the construction of a canal radiating southward from Angkor Borei during its period of peak occupation in the early centuries A.D. Our work has also identified changing vegetational patterns in the 5th century AD that may be related to changing settlement demographics at Angkor Borei (Article). We continue to explore both these topics in our current LOMAP field investigations.

Work also continues on the large encircling earthen/brick wall around the site of Angkor Borei. Once thought to date to the site’s earliest occupation, we are now exploring its timing in the site’s occupational history. Obtaining dates for the brick wall construction may shed light on the introduction of brick architecture into the Mekong delta. Recent Vietnamese research on brick architecture at "Oc Eo culture" sites dated construction fill associated with the structures to date them. Direct dating of brick should provide more accurate ages for the buildings. We also cleared back a previous wall cut to study the wall's construction sequence, and excavated a 1 m x 2 m unit beneath the exposed surface to study the construction sequence of the wall itself. Preliminary analysis of the wall stratigraphy suggests (but does not prove) that the brick wall that so prominently surrounds Angkor Borei today may have been built atop an earlier earthen embankment.

Constructing Regional Settlement Histories: the LOMAP 2003-2009 Archaeological Survey Project

Understanding the occupational history and changing scale of Angkor Borei is the first step to exploring state formation in Cambodia’s Mekong delta. Yet such research is incomplete without an understanding of changing settlement patterns in the broader region, and the role that this center played in such changes. Accordingly, the LOMAP Archaeological Survey was undertaken in three field seasons from 2003 and 2005. The construction and use of a GIS database that incorporates a range of remote sensing data was instrumental to identifying survey areas for fieldwork and modeling potential site catchments across the broader Takeo region. Regional-level analysis and development of site locational models is currently underway at the University of Hawai'i-Manoa.

This large-site survey project concentrated its efforts on areas flanking the Takeo river that runs southeast of Angkor Borei and into Vietnam. Part of our fieldwork work involved recording sites that the French reported (but did not document) during the early 20th century. Our 2003 field season focused on sites adjacent to the river and on a series of sites immediately NW of Angkor Borei. In 2004, we expanded our coverage to the west along the fringes of the Takeo River floodplain. We moved west away from the river for the 2005 field season, and also began exploring the region between Phnom Chisor (to the north) and Angkor Borei (to the south). All of these regions had large numbers of moated mounds in various configurations that we mapped and photographed.

We identified three primary site types (i.e., moat-mounds, artifact concentrations, and water control features); in some cases, site clusters contained all three configurations. The vast majority of sites we documented had one or more moated mounds, and these were commonly located away from contemporary Khmer villages in prime agricultural areas. In a few cases, the moated mounds were found directly adjacent to the villages, and the villages (but not the mounds themselves) also contained subsurface ceramic deposits that suggest a pre-Angkorian residential function.

Whether most of these moated mounds originally housed brick constructions remains unclear. In his early 20th century survey of the region, Lunet de la Jonquière reported that most brick shrines had already been dismantled. Many mounds that the LOMAP 2003-2005 field season visited contained some brick fragments; a smaller number contained portions of brick architecture. Most brick localities that we documented were quite fragmentary, and finding intact masonry was difficult.

The “site” category used during the LOMAP survey is somewhat complex, because some moat-mounds along the Takeo River appeared in complexes. Here we illustrate the example of Kampong Youl, which is a contemporary Cham settlement that sits atop a mound complex. Few of these mound complexes bear little evidence of subsurface ceramics, which certainly suggests that moated mounds did not serve a predominantly residential function. That mounds formed clusters, and clusters formed something like “sites’” is clear. So, too, is the relationship of clusters to one another. Here we can see two examples of clusters along the Takeo River that have contemporaneous ceramic assemblages. Our next step is to characterize variability in these mounds and clusters to understand their configurations and the relationship of moated mounds to residential areas. We will also characterize the potential land-use strategies around each residential site to begin reconstructing the ancient farming systems that supported the growing delta populations of the first millennium AD.

Predictive Modeling of Site Locations and the Next LOMAP Step

A growing body of archaeological evidence supports the French claim that Angkor Borei was a large regional center during the period we associate with Funan, and that its importance continued throughout the pre-Angkorian period. Analyzing data from the 2003-2005 survey region offers intriguing clues regarding changing settlement patterns through time through the northern Mekong delta, but more work is needed to the north and west of our survey area. Funding from a NASA Space Archaeology grant took LOMAP crew members back to Takeo Province in July and August 2009 to apply results of predictive models now under development.

LOMAP gratefully acknowledges funding and logistical support from the following institutions:

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration Space Archaeology Program

- National Science Foundation Archaeology Program

- National Endowment for the Humanities International Collaborative Research Program

- National Geographic Society Grants for Scientific Research and Exploration Program

- Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research International Collaborative Research Program

- Center for Khmer Studies

- Foundation for Research and Exploration on Cultural Origins

- East-West Center Indochina Initiative

- University of Hawai’i-Manoa

Historic Preservation and Heritage Management at Angkor Borei

LOMAP is also dedicated to historic preservation and heritage management at Angkor Borei, working collaboratively with colleagues from the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts, and with officials at the district and provincial levels. In 1994, Cambodia's heritage officials selected Angkor Borei for LOMAP because of its historical importance, political stability, and accessibility from Phnom Penh. Work at this site, however, underscores the intimate relationship between heritage management and preservation, on the one hand, and heritage destruction (looting) and cultural tourism on the other. The site of Angkor Borei is located a few kilometers from Cambodia's border with Vietnam. Riverine traffic between Vietnam and Cambodia is continuous: people, their animals, and their goods move into and out of this Angkor Borei en route to (or arriving from) Vietnam. The community's key location and large size makes it ideal for trafficking goods, both legal and contraband. According to interviews with local villagers and with officials, the looting of the settlement's archaeological past extends back at least a decade.

Before 1970, antiquities were revered in Cambodia as they were in much of Buddhist Southeast Asia: Indic statues and artifacts were stored and venerated in Buddhist temples across the country. French collectors visited these temples in the 1930s and took most 7th and 8th century (pre-Angkorian) Indic statues for museum collections in Cambodia and France. More statuary moved onto the international art market since 1993, and Angkor Borei/Phnom Da style sculptures are now occasionally available for purchase on the web. After the 1993 elections, local people report that outsiders began to visit Angkor Borei in search of antiquities. The rising demand for antiquities was irresistible to the military troops stationed in the region, and villagers report that they were given screens to use in their excavations of areas that might yield gold. In interviews with LOMAP members in 1999, the head monk of the Buddhist temple at Phnom Da (the hill with temples south of Angkor Borei) reported that he was approached with armed villagers and ordered to relinquish antiquities that were stored at his temple.

The continuing damage to Angkor Borei's archaeological heritage is a source of genuine concern to the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts; the ministry asked LOMAP to develop an integrated site protection and historic preservation program for the site. Our archaeological field investigations at Angkor Borei attracted great attention to the area by its local inhabitants, and we have begun to make public presentations to, and interact with, the community through the schools and the local temples. In 1999 and 2000, we also conducted tours to cohorts of archaeology and architecture students from the Royal University of Fine Arts (Phnom Penh) throughout the field season. Lack of information -- and, indeed, lack of education about Cambodian history -- is one major obstacle to site protection at Angkor Borei. Angkor Borei's proximity to Phnom Penh (if the roads are repaired) and its cultural significance to the Khmers make Angkor Borei an excellent candidate for protection and tourism development.

One of the European Union's agricultural development programs, PRASAC (Programme de Réhabilitation et d'Appui au Secteur Agricole du Cambodge), began this effort toward tourism development in 1997 by constructing an on-site museum at Angkor Borei. Collaborative efforts between PRASAC and the Lower Mekong Archaeological Project since then have worked on public education and historic preservation of the site. These efforts include the development of exhibits concerning the LOMAP work and Angkor Borei that are housed at the onsite museum and work toward developing a zoning and management plan that would protect areas surrounding the site in a sustainable fashion. PRASAC has also helped LOMAP to construct protective walls and barriers to prevent areas of Angkor Borei from environmental damage and looting.

Cambodia's archaeological heritage is vital to its people, and the archaeological heritage of Angkor Borei is valuable to many different constituencies. To archaeologists, its resources hold a story that describes the origins of the earliest civilizations in the Mekong delta. To school teachers and educators, Angkor Borei represents the cradle of Khmer civilization and the Khok Thlok of oral traditions. To Cambodian and foreign tourists, Angkor Borei and Phnom Da represent an intriguing destination to learn about Cambodia's ancient past. The challenge now is to learn from it and to preserve it, and the artifacts from this site that appear on the global market -- for Cambodia's future generations.

Contributions of the UH/EWC/RUFA Cambodia and Lower Mekong Archaeological Projects

One contribution of the project concerns the heightened publicity that this commitment to long-term, field research should brings to the Cambodian archaeological heritage. Project researchers work actively with staff and students from both the National Museum of the Kingdom of Cambodia and the Royal University of Fine Arts. Our hope is that the combined efforts of the Cambodia project will also help to stem rampant vandalism at the region's largest and most important archaeological sites.

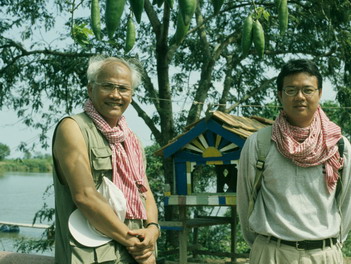

In December 2003, Cambodian graduate student Bong Sovath (on right in photograph; LOMAP co-director H.E. Chuch Phoeurn on left, 2001) just completed his Ph.D., making him the first Cambodian to receive a doctoral degree in archaeology. Our active recruitment program for additional Cambodian graduate students continues. Within Cambodia itself, alumni of the LOMAP program have joined cultural heritage management programs throughout the country, and are becoming senior researchers and administrators in Cambodia's archaeology and historic preservation divisions. With world-class monuments such as the Angkor Wat Historical Park, these Cambodian scholars will be well equipped to open a new chapter in the archaeology of Southeast Asia.

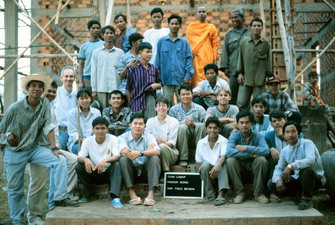

The UHM Anthropology program is pleased to currently host Mr. Heng Piphal (in photograph with Stark in 2004), who is completing his MA degree with Fulbright funding. Several current UHM Anthropology graduate students are pursuing Cambodia-related archaeological research at present. We hosted Mr. Chan Sovichetra for the 2008-2009 academic year and Mr. Chhay Rachna for the 2009-2010 academic year through the Luce Asian Archaeological Program and look forward to continued educational opportunities for Cambodian and non-Cambodian students to study with us at the University of Hawai’i-Manoa.

International, collaborative research and training go hand-in-hand in the Lower Mekong Archaeological Project. Prospective graduate students and colleagues are invited to join us in these endeavors, and are encouraged to contact LOMAP Co-Director Dr. Miriam Stark (miriams@hawaii.edu).